|

|

|

The basis of this text

is taken from the article "Recording Methods", part of the "Album

That Never Was" page on my Johnny

Kidd and the Pirates site.

|

|

|

EMI

Studios, Abbey Road |

Although

mono was still King in the UK in the late 1950's (and would remain so

for some years yet) the Abbey Road studios staff were well versed in

recording large orchestras "live" onto a twin-track stereo machine for a

virtually immediate stereo mastered product. The large sound accordingly

filled the spectrum between the left and right channels. For a raw rock

band consisting of four instruments plus singer a similar but economical

"live" method would be employed where a few microphones were set up.

Sometimes it was even more basic: the Capitol Studio where Gene

Vincent's early stuff was recorded featured a single microphone, singer

and instruments being distanced according to their relative volumes.

Later on, the singer would have his/her own mike to help the sound

engineers "lift" the volume of his voice (either during recording or

mixdown) so he could be heard properly.

By

comparison early Rock music was considered not "real" music,

more a passing 'fad' by the

establishment thus it didn't qualify for quite so much time being spent on it.

Typically, a three-hour session would be arranged, enough for both sides

of the next single - often with one or two extra cuts (for an EP or LP,

should sales allow) - time was money, after all. You had to get it right

in the studio as once you captured it on tape, that was basically it.

Later on the widespread use of tape allowed more flexible editing

techniques to be used; a Post-production session could then remove bum

notes and apply basic equalising if necessary.

Rock

mellowed into a more commercial "Pop" and using the twin-track

machines to separate band from vocals allowed the engineer, given time,

to play with the sound on each track, with a bit of EQ here, a touch

more volume there, etc, so the best mono mix could be obtained to give a

better, punchier sound for bigger sales. Before long the more

adventurous engineers began recording the backing track - instruments

only - on one track. The best "take" would then have the

vocals "overdubbed" on the adjacent track until a satisfactory

"take" had been achieved. Either then or at a separate

"mixing" session the tracks would be blended into the one mono

master for cutting into a 7-inch single. Each analogue tape copying

increases the amount of distortion and the quality will eventually

suffer as each generation adds it's own artifacts which, after much copying

becomes increasingly distracting. Rock

mellowed into a more commercial "Pop" and using the twin-track

machines to separate band from vocals allowed the engineer, given time,

to play with the sound on each track, with a bit of EQ here, a touch

more volume there, etc, so the best mono mix could be obtained to give a

better, punchier sound for bigger sales. Before long the more

adventurous engineers began recording the backing track - instruments

only - on one track. The best "take" would then have the

vocals "overdubbed" on the adjacent track until a satisfactory

"take" had been achieved. Either then or at a separate

"mixing" session the tracks would be blended into the one mono

master for cutting into a 7-inch single. Each analogue tape copying

increases the amount of distortion and the quality will eventually

suffer as each generation adds it's own artifacts which, after much copying

becomes increasingly distracting.

On

the other hand Joe Meek, the maverick independent producer ("Telstar", "Johnny Remember

Me") had tracked this way and more for years. Using two tape

machines, one a twin-track job, he would record a bands' rhythm section,

copy the result onto the other machine adding various additional

instruments, finally the vocals, even 'bounced' back again in order to

double-track the vocals. A Joe Meek

production may have been bounced back and forth in this fashion up to six

times. The heavy compression 'pumps' the sound and quiet split-seconds

heave their way up in the mix with all the tape hiss this

over-processing allowed. In this way Meeks' methods make a feature out

of compression and distortion which went totally against the grain. And the power literally jumped out of the speakers at you.

When

4-track recording arrived at Abbey Road Studios

in late 1963 it meant greater flexibility and control - the demanding

Beatles couldn't wait to play but had to wail until the chief

technicians had worked out what it was capable of. Where previously George Martin

and his staff had used his

experience and ingenuity to overdub the odd extra vocal or instrument to good

effect they were now able to record the backing track and extras as

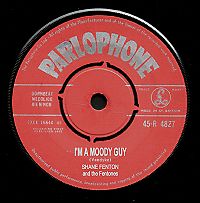

required without altering anything already perfectly recorded. Shane

Fenton's later recordings would almost certainly be tracked this way

with the odd exception, especially after 1963. The Beatles reached

4-tracks zenith quickly as their songwriting became ever more complex;

Songs like "Hello Goodbye" feature tape 'reductions', the four

full tracks would be copied to another 4-track machine in a mixdown

fashion freeing more tracks on the second tape for the continued

overdubbing. Up to four of these operations occurred on any one tune -

and we're back to the engineers trying to prevent too much distortion

creeping onto tape with each copy.

Thankfully,

it was only a matter of time before 8-track, then 16-track machines were

introduced, and the only copying process would be in the mixdown from multitrack tape to stereo masters

(mono would be all but obsolete in a couple of years). Too far in the

future for Shane Fenton and co. whose recording career (released

material anyhow) ended in 1964. Had any one of their latter singles, say

"Don't Do That" or Hey Lulu" been the smash they were

waiting for I wonder whether they would have made of the new technology

offered in terms of recording freedom? They sadly didn't get a chance of

an album when they were a chart act so we will never know. In just a

couple of years time groups would start emerging who specialised in albums rather

than having a dependency on the top 50.

|

|